SMS Stettin

SMS Stettin in 1912

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Stettin |

| Namesake | Stettin |

| Builder | AG Vulcan, Stettin |

| Laid down | 1906 |

| Launched | 7 March 1907 |

| Commissioned | 29 October 1907 |

| Stricken | 5 November 1919 |

| Fate | Ceded to Britain 1920, scrapped in 1921–1923 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Königsberg-class light cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 115.3 m (378 ft) |

| Beam | 13.2 m (43 ft) |

| Draft | 5.29 m (17.4 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 24 knots (44.4 km/h; 27.6 mph) |

| Range | 5,750 nautical miles (10,650 km; 6,620 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Stettin ("His Majesty's Ship Stettin")[a] was a Königsberg-class light cruiser of the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). She had three sister ships: Königsberg, Nürnberg, and Stuttgart. Laid down at AG Vulcan Stettin shipyard in 1906, Stettin was launched in March 1907 and commissioned into the High Seas Fleet seven months later in October. Like her sisters, Stettin was armed with a main battery of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) guns and a pair of 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes, and was capable of a top speed in excess of 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph).

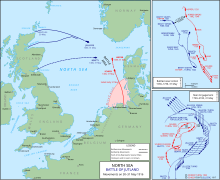

In 1912, Stettin joined the battlecruiser Moltke and cruiser Bremen for a goodwill visit to the United States. After the outbreak of World War I, Stettin served in the reconnaissance forces of the German fleet. She saw heavy service for the first three years of the war, including at the Battle of Heligoland Bight in August 1914 and the Battle of Jutland in May – June 1916, along with other smaller operations in the North and Baltic Seas. In 1917, she was withdrawn from frontline service and used as a training ship until the end of the war. In the aftermath of Germany's defeat, Stettin was surrendered to the Allies and broke up for scrap in 1921–1923.

Design[edit]

The Königsberg-class ships were designed to serve both as fleet scouts in home waters and in Germany's colonial empire. This was a result of budgetary constraints that prevented the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) from building more specialized cruisers suitable for both roles.[1] The Königsberg class was an iterative development of the preceding Bremen class. All four members of the class were intended to be identical, but after the initial vessel was begun, the design staff incorporated lessons from the Russo-Japanese War. These included internal rearrangements and a lengthening of the hull. Stettin was fitted with steam turbines on an experimental basis; she was the second cruiser of the German fleet.[2][3]

Stettin was 115.3 meters (378 ft) long overall and had a beam of 13.2 m (43 ft) and a draft of 5.29 m (17.4 ft) forward. She displaced 3,814 t (3,754 long tons; 4,204 short tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of a pair of Parsons steam turbines with steam provided by eleven coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boilers. These provided a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph) and a range of approximately 5,750 nautical miles (10,650 km; 6,620 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Stettin had a crew of 14 officers and 308 enlisted men.[4]

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/40 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side-by-side forward on the forecastle, six were located amidships, three on either side, and two were side by side aft. The guns had a maximum elevation of 30 degrees, which allowed them to engage targets out to 12,700 m (41,700 ft).[5] They were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition, amounting to 150 shells per gun. The ship was also equipped with eight 5.2 cm (2 in) SK guns with 4,000 rounds of ammunition. She was also equipped with a pair of 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes with five torpedoes submerged in the hull on the broadside. The ship was protected by an armored deck that was 80 mm (3.1 in) thick amidships. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides.[4]

Service history[edit]

Stettin was ordered under the contract name "Ersatz Wacht"[b] on 20 December 1905. She was laid down at the AG Vulcan shipyard in her namesake city on 22 March 1906. She was launched on 7 March 1907, and the mayor of Stettin gave a speech at the launching ceremony. Fitting-out work thereafter commenced, which was completed by September 1907. Because of her experimental turbines, the German Navy examined the ship thoroughly before accepting her. She was commissioned into active service on 29 October to begin sea trials. Following her initial testing, she was assigned to the Scouting Unit on 20 January 1908, replacing the cruiser Frauenlob. In February, she and the rest of the scouting unit visited Vigo, Spain, during a cruise with the High Seas Fleet. Stettin's normal peacetime routine of training exercises was interrupted from 17 June to 8 August, when she was ordered to escort Hohenzollern, the yacht of Kaiser Wilhelm II. During this period, the ships sailed to Stockholm, Sweden, where the Swedish king, Gustav V visited Stettin.[6][7]

In early 1909, civil unrest broke out in the Ottoman Empire against Christians living in the country. At the time, Hohenzollern was cruising in the Mediterranean Sea with the cruiser Hamburg as the escort. Hamburg was detached to intervene in southern Anatolia in the Ottoman Empire, and Stettin was sent to replace her as the escort for Hohenzollern. On 9 April, she departed Kiel in company with the light cruiser Lübeck, which was to support Hamburg in operations off the coast of Anatolia. The ships arrived in Corfu, an island off Greece, on 1 May. While the ships were in Pola, Austria-Hungary, on 15 May, Stettin received orders to return to Germany. She reached Kiel on 26 May. Stettin once again served as the escort for Hohenzollern in 1910, from 7 to 30 July. This year, the ships cruised in Scandinavian waters. The year 1911 passed uneventfully for Stettin, beyond the normal peacetime routine of training exercises and fleet maneuvers.[3]

In March 1912, Stettin was assigned to the East American Cruiser Division, which also included the battlecruiser Moltke and the light cruiser Bremen, and was commanded by Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz. The ships were sent to makea goodwill cruise to the United States; Moltke was the only German capital ship to ever visit the US. On 11 May 1912 the ships left Kiel and arrived off Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 30 May. There, they met the US Atlantic Fleet and were greeted by then-President William Howard Taft aboard the presidential yacht USS Mayflower. After touring the East Coast for two weeks, they returned to Germany. On the way back, they stopped in Vigo from 22 to 26 June, before continuing on to Kiel, arriving there three days later. Stettin thereafter returned to the reconnaissance unit.[3][8][9]

In July 1913, Stettin was sent to Pillau for a ceremony for the dedication of a monument for Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg. Later that year, she was involved in a minor collision with the steam ship SS Cassandra, and Stettin had one of her spotting tops torn off a mast. The ship took part in her last peacetime training exercise with the High Seas Fleet in November 1913. She was thereafter replaced in the reconnaissance unit by the new cruiser Rostock, and on 4 February 1914, Stettin had her crew reduced. On 1 July, the ship was reactivated and received a full crew; she was now to join the U-boat force as a submarine flotilla flagship. Stettin became the flagship of II U-boat Flotilla.[3] By that time, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary had been assassinated, which sparked the July Crisis and led to the outbreak of World War I in late July, starting with the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia on the 28th.[10]

Actions in the North Sea[edit]

Stettin continued in her role as a U-boat flotilla flagship after the start of hostilities. On 6 August, she and the cruiser Hamburg escorted a flotilla of U-boats into the North Sea in an attempt to draw out the British fleet, which could then be attacked by the U-boats. The force sailed about 100 nautical miles (190 km; 120 mi) to the northwest of Helgoland and then returned to port without having encountered any British warships. They made a second sweep into the North Sea on 8 August, again without successfully locating any British ships.[3][11] Some two weeks later, on 28 August, Stettin was involved in the Battle of Helgoland Bight. At the start of the engagement, Stettin, Frauenlob, and Hela stood in support of the line of torpedo boats patrolling the Helgoland Bight; Stettin was at anchor to the northeast of Helgoland, and the other two ships were on either side. The German screen was under the command of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, the commander of reconnaissance forces for the High Seas Fleet.[12]

When the British first attacked the German torpedo boats, Hipper immediately dispatched Stettin and Frauenlob, and several other cruisers that were in distant support, to come to their aid. At 08:32, Stettin received the report of German torpedo boats in contact with the British, and immediately weighed anchor and steamed off to support them. Twenty-six minutes later, she encountered the British destroyers and opened fire, at a range of 8.5 km (5.3 mi). The attack forced the British ships to break off and turn back west. During the engagement, lookouts aboard Stettin spotted a British cruiser in the distance, but it did not join the battle. By 9:10, the British had withdrawn out of range, and Stettin fell back to get steam in all of her boilers. During this portion of the battle, the ship was hit once, on the starboard No. 4 gun, which killed two men and badly injured another. Her intervention prevented the British from sinking the torpedo boats V1 and S13.[13]

By 10:00, Stettin had steam in all of her boilers, and was capable of her top speed. She therefore returned to the battle, and at 10:06, she encountered eight British destroyers and immediately attacked them, opening fire at 10:08. Several hits were observed in the British formation, which dispersed and fled. By 10:13, the visibility had decreased, and Stettin could no longer see the fleeing destroyers, and so broke off the chase. The ship had been hit several times in return, without causing significant damage, but killing another two and wounding another four men. At around 13:40, Stettin reached with the cruiser Ariadne, which was just coming under attack from several British battlecruisers. Stettin's crew could see the large muzzle flashes in the haze, which after having disabled Ariadne, turned on Stettin at 14:05. The haze saved the ship, which was able to escape after ten salvos missed her. At 14:20, she encountered Danzig. The German battlecruisers Von der Tann and Moltke reached the scene by 15:25, by which time the British had already disengaged and withdrawn. Hipper, in Seydlitz, followed closely behind, and ordered the light cruisers to fall back on his ships. After conducting a short reconnaissance further west, the Germans returned to port, arriving in Wilhelmshaven by 21:30.[14] In total, Stettin had two men killed and nine wounded.[3]

Stettin was removed from her role as flotilla flagship on 25 November, and two days later, she was assigned to IV Scouting Group, part of the reconnaissance screen for the battleships of the High Seas Fleet. She became the group flagship, under the command of Kommodore (Commodore) Karl von Restorff. At that time, Restorff was also the commander of II Torpedo-boat Flotilla. In this new role, Stettin became involved in the raids on the British coast that were carried out by the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group.[15] The first that involved Stettin began on 15 December, when I Scouting Group, led by Hipper, conducted a bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby on the English coast. The main body of the High Seas Fleet, commanded by Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, stood by in distant support; Stettin and two flotillas of torpedo boats screened the rear of the formation.[16] That evening, the German battle fleet of some twelve dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts came to within 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) of an isolated squadron of six British battleships. However, skirmishes between the rival screens in the darkness convinced Ingenohl that he was faced with the entire Grand Fleet. Under orders from Kaiser Wilhelm II to avoid risking the fleet unnecessarily, Ingenohl broke off the engagement and turned the battle fleet back toward Germany.[17]

On 26 January 1915, Restorff's commands were divided; he retained control over II Torpedo-boat Flotilla and shifted his flag to the cruiser Kolberg, while KzS Georg Scheidt replaced him as commander of IV Scouting Group. Scheidt, who was promoted to konteradmiral on 23 February, kept Stettin as the group flagship. At that time, the unit consisted of Stettin and the cruisers Stuttgart, Danzig, Berlin, München, and Frauenlob. Stettin next went to sea for a fleet operation on 29 March, though IV Scouting Group was missing Danzig and Stuttgart; they were instead reinforced with Hamburg. The operation concluded the following day, and failed to locate British vessels. On 11 April, Stettin, München, and Frauenlob sortied to cover a patrol by the 2nd and 13th Torpedo-Half-Flotillas to the area south of Horns Rev to inspect fishing boats in the area. Two further fleet operations into the North Sea followed on 17–18 and 21–22 April, again without resulting in action with British forces.[18]

Operations in the Baltic[edit]

On 4 May 1915, IV Scouting Group, which by then consisted of Stettin, Stuttgart, München, and Danzig, and twenty-one torpedo boats was sent into the Baltic Sea to support a major operation against Russian positions at Libau. The operation was commanded by Rear Admiral Hopman, the commander of the reconnaissance forces in the Baltic. IV Scouting Group was tasked with screening to the north to prevent any Russian naval forces from moving out of the Gulf of Finland undetected, while several armored cruisers and other warships bombarded the port. The ships of IV Scouting Group were ordered to patrol the line between Huvudskär, Gotska Sandön, and Ösel.[18][19]

The Russians did attempt to intervene with a force of four cruisers: Admiral Makarov, Bayan, Oleg, and Bogatyr. The Russian ships briefly engaged München, and Scheidt recalled his other cruisers to join Stettin to come to München's aid. The Russian forces were significantly stronger than the German light cruisers, but they believed more powerful German forces would intervene, and so they disengaged; indeed, when reports of the action arrived at German headquarters, the pre-dreadnought battleships of IV Battle Squadron were detached to reinforce Scheidt's cruisers. Shortly after the bombardment, Libau was captured by the advancing German army, and Stettin and the rest of IV Scouting Group were recalled to the High Seas Fleet, arriving back in the North Sea on 12 May.[18][20]

Return to the North Sea[edit]

Soon after arriving back with the High Seas Fleet, Stettin and the rest of IV Scouting Group sortied for another sweep into the North Sea on 17–18 May. Another attempt to catch British vessels in the southern North Sea took place on 29–30 May. Neither operation located hostile ships. The pace of operations slowed somewhat, and on 2 July, Stettin again served in the covering force for a torpedo-boat patrol among the fishing ships south of Horns Rev. On 10 August, the fleet went to sea again, this time to cover the return of the auxiliary cruiser Meteor, which was returning from a commerce raiding cruise. Kommodore Ludwig von Reuter replaced Scheidt as the group commander on 3 September. Stettin covered a minelaying operation off the Swarte Bank on 11–12 September. The final fleet operation of the war took place on 23–24 October in the direction of Horns Rev; like its predecessors, the ships did not encounter British vessels.[18]

The German fleet saw little activity over the winter of 1915–1916. The first major operation carried out by Stettin and the rest of IV Scouting Group took place on 4 March, and it was a patrol to cover the return of the commerce raider Möwe. The following day, the ships joined the main body of the High Seas Fleet for a sweep into the Hoofden that concluded on 7 March, again without result. Stettin was dry docked for periodic maintenance from 8 to 25 March. Reuter temporarily left the ship on 28 March, as he was briefly transferred to command II Scouting Group. Kommodore Paul Heinrich, the commander of II Torpedo-boat Flotilla, was given command of IV Scouting Group in Reuter's absence, which lasted until 13 May, when Reuter returned to Stettin. By this time, the unit consisted of Stettin, Stuttgart, Frauenlob, and München; in addition, Hamburg, which was the flagship of the fleet's torpedo boat flotillas, was tactically assigned to IV Scouting Group.[18]

Battle of Jutland[edit]

In May 1916, the German fleet commander, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, planned a major operation to cut off and destroy an isolated squadron of the British fleet. The operation resulted in the battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916.[21] IV Scouting Group was tasked with screening for the main German battlefleet. As the German fleet approached the scene of the unfolding engagement between the British and German battlecruiser squadrons, Stettin steamed ahead of the leading German battleship, König, with the rest of the Group dispersed to screen for submarines. Stettin and IV Scouting Group were not heavily engaged during the early phases of the battle, but around 21:30, they encountered the British cruiser HMS Falmouth. Stettin and München briefly fired on the British ship, but poor visibility forced the ships to cease fire. Reuter turned his ships 90 degrees away and disappeared in the haze.[22]

During the withdrawal from the battle on the night of 31 May at around 23:30, the battlecruisers Moltke and Seydlitz passed ahead of Stettin too closely, forcing her to slow down. The rest of IV Scouting Group did not notice the reduction in speed, and so the ships became disorganized. Shortly thereafter, the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron came upon the German cruisers, which were joined by Hamburg, Elbing, and Rostock. A ferocious firefight at very close range ensued; Stettin was hit twice early in the engagement and was set on fire. A shell fragment punctured the steam pipe for the ship's siren, and the escaping steam impaired visibility and forced the ship to abandon an attempt to launch torpedoes. In the melee, HMS Southampton was hit by approximately eighteen 10.5 cm shells, including some from Stettin. In the meantime, the German cruiser Frauenlob was set on fire and sunk; as the German cruisers turned to avoid colliding with the sinking wreck, IV Scouting Group became dispersed. Only München remained with Stettin. The two ships accidentally attacked the German destroyers G11, V1, and V3 at 23:55.[23]

By 04:00 on 1 June, the German fleet had evaded the British fleet and reached Horns Reef; the Germans then returned to port.[24] In the course of the battle, Stettin had suffered eight men killed and another 28 wounded. She had fired a total of 81 rounds of ammunition from her 10.5 cm guns.[25]

Fate[edit]

In 1917, Stettin was withdrawn from front line service and used as a training ship with the U-boat school.[26] She served in this capacity until the end of the war.[27] Under Article 185 of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war after the Armistice that ceased fighting on 11 November 1918, Stettin was listed among the warships still in German service that were to be surrendered to the Allied powers,[28] and accordingly she was stricken on 5 November 1919. She was surrendered to Great Britain as a war prize on 15 September 1920, under the transfer name "T". She was then sold to shipbreakers in Copenhagen and dismantled for scrap in 1921–1923.[27]

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ German warships were ordered under provisional names. For new additions to the fleet, they were given a single letter; for those ships intended to replace older or lost vessels, they were ordered as "Ersatz (name of the ship to be replaced)".

Citations[edit]

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, pp. 142, 157.

- ^ Nottelmann, pp. 110–114.

- ^ a b c d e f Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 188.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 104.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, pp. 140, 157.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Staff 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Hadley & Sarty, p. 66.

- ^ Heyman, p. xix.

- ^ Scheer, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Staff 2011, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Staff 2011, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Staff 2011, pp. 10–11, 21–22, 26.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Scheer, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- ^ a b c d e Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 189.

- ^ Halpern, p. 191.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 61.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 35, 251–252.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 276, 280–284, 390.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 341, 360.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 157.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 105.

- ^ Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185

References[edit]

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hadley, Michael L.; Sarty, Roger (1995). Tin-pots and Pirate Ships: Canadian Naval Forces and German Sea Raiders, 1880–1918. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-304-35848-7.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Heyman, Neil M. (1997). World War I. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29880-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. OCLC 310653560.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 2765294. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84884-182-6.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-35848-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.