Portal:Scotland/Featured

The Scotland Portal

View from An Teallach

| Main Page | Selected articles 1 | Selected articles 2 | Selected biographies | Selected quotes | Selected pictures | Featured Content | Categories & Topics |

Selection of featured articles

Selection of good articles

Arbroath (/ɑːrˈbroʊθ/) or Aberbrothock (Scottish Gaelic: Obar Bhrothaig [ˈopəɾ ˈvɾo.ɪkʲ]) is a former royal burgh and the largest town in the council area of Angus, Scotland, with a population of 23,902. It lies on the North Sea coast, some 16 miles (26 km) east-northeast of Dundee and 45 miles (72 km) south-southwest of Aberdeen.

There is evidence of Iron Age settlement, but its history as a town began with the founding of Arbroath Abbey in 1178. It grew much during the Industrial Revolution through the flax and then the jute industry and the engineering sector. A new harbour was created in 1839; by the 20th century, Arbroath was one of Scotland's larger fishing ports. (Full article...)

Scottish society in the Middle Ages is the social organisation of what is now Scotland between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Social structure is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources. Kinship groups probably provided the primary system of organisation and society was probably divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare, a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes, above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

From the twelfth century there are sources that allow the stratification in society to be seen in detail, with layers including the king and a small elite of mormaers above lesser ranks of freemen and what was probably a large group of serfs, particularly in central Scotland. In this period the feudalism introduced under David I meant that baronial lordships began to overlay this system, the English terms earl and thane became widespread. Below the noble ranks were husbandmen with small farms and growing numbers of cottars and gresemen (grazing tenants) with more modest landholdings. The combination of agnatic kinship and feudal obligations has been seen as creating the system of clans in the Highlands in this era. Scottish society adopted theories of the three estates to describe its society and English terminology to differentiate ranks. Serfdom disappeared from the records in the fourteenth century and new social groups of labourers, craftsmen and merchants, became important in the developing burghs. This led to increasing social tensions in urban society, but, in contrast to England and France, there was a lack of major unrest in Scottish rural society, where there was relatively little economic change. (Full article...)

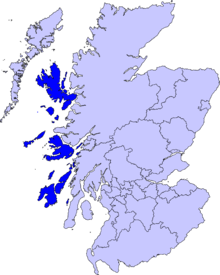

The Outer Hebrides (/ˈhɛbrɪdiːz/ HEB-rid-eez) or Western Isles (Scottish Gaelic: na h-Eileanan Siar [nə ˈhelanən ˈʃiəɾ] , na h-Eileanan an Iar [nə ˈhelanən əɲ ˈiəɾ] or na h-Innse Gall, 'Islands of the Strangers'; Scots: Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (Scottish Gaelic: an t-Eilean Fada), is an island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland. The islands are geographically coextensive with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland. They form part of the archipelago of the Hebrides, separated from the Scottish mainland and from the Inner Hebrides by the waters of the Minch, the Little Minch, and the Sea of the Hebrides.

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from ancient metamorphic rocks, and the climate is mild and oceanic. The 15 inhabited islands have a total population of 26,120 and there are more than 50 substantial uninhabited islands. The distance from Barra Head to the Butt of Lewis is roughly 210 kilometres (130 mi). (Full article...)

The Jocky Wilson Cup (officially the PartyPoker.com Jocky Wilson Cup for sponsorship) was a professional darts team tournament that took place at the Braehead Arena in Glasgow, Scotland, on 5 December 2009. This one-off tournament, which was named after Jocky Wilson, a two-time world darts champion, was the last of the eight non-ranking Professional Darts Corporation (PDC) events of the 2009 season. The tournament was contested by two nations of two players each. The winning nation was the first country to earn four points over a five-match series – four singles fixtures and one doubles game.

Phil Taylor and James Wade of England won the competition and whitewashed their opponents Gary Anderson and Robert Thornton of Scotland 6–0. Wade won the first game against Anderson 6–4; Taylor beat Thornton 6–0 in the second. Wade and Taylor defeated their opponents in the doubles match 6–2 for the overall victory and won their final two singles matches 6–4 over their Scottish opponents. (Full article...)

Phil Taylor and James Wade of England won the competition and whitewashed their opponents Gary Anderson and Robert Thornton of Scotland 6–0. Wade won the first game against Anderson 6–4; Taylor beat Thornton 6–0 in the second. Wade and Taylor defeated their opponents in the doubles match 6–2 for the overall victory and won their final two singles matches 6–4 over their Scottish opponents. (Full article...)

}

'"`UNIQ--templatestyles-00000049-QINU`"'

'"`UNIQ--references-0000004A-QINU`"'

Source: (Full article...)

'"`UNIQ--templatestyles-00000049-QINU`"'

'"`UNIQ--references-0000004A-QINU`"'

Source: (Full article...)

The Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 (24 Geo. 2. c. 23), also known as Chesterfield's Act or (in American usage) the British Calendar Act of 1751, is an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. Its purpose was for Great Britain and the British Empire to adopt the Gregorian calendar (in effect). The Act also rectified other dating anomalies, such as changing the start of the legal year from 25 March to 1 January.

The Act elided eleven days from September 1752. It ordered that religious feast days be held on their traditional dates – for example, Christmas Day remained on 25 December. (Easter is a moveable feast: the Act specifies how its date should be calculated.) It ordered that civil and market days – for example the quarter days on which rent was due, salaries paid and new labour contracts agreed – be moved forward in the calendar by eleven days so that no-one should gain or lose by the change and that markets match the agricultural season. It is for this reason that the UK personal tax year ends on 5 April, being eleven days on from the original quarter-day of 25 March (Lady Day). (Full article...)

The Act elided eleven days from September 1752. It ordered that religious feast days be held on their traditional dates – for example, Christmas Day remained on 25 December. (Easter is a moveable feast: the Act specifies how its date should be calculated.) It ordered that civil and market days – for example the quarter days on which rent was due, salaries paid and new labour contracts agreed – be moved forward in the calendar by eleven days so that no-one should gain or lose by the change and that markets match the agricultural season. It is for this reason that the UK personal tax year ends on 5 April, being eleven days on from the original quarter-day of 25 March (Lady Day). (Full article...)

Sundrum Castle is a Scottish medieval castle located 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) north of Coylton, South Ayrshire, by the Water of Coyle river. It was built in the 14th century for Sir Duncan Wallace, Sheriff of Ayr. The castle was inherited by Sir Alan de Cathcart, who was the son of Duncan's sister. The Cathcarts sold Sundrum in the 18th century, where it eventually fell into the possession of the Hamilton family. The Hamiltons expanded the castle in the 1790s, incorporating the original keep into a mansion.

The castle was further expanded in the early 20th century by Ernest Coats. For a time it was a hotel, but fell into disrepair. It became a category B listed building in 1971. After extensive renovations in the 1990s, it was split into several privately owned properties. (Full article...)

James I (late July 1394 – 21 February 1437) was King of Scots from 1406 until his assassination in 1437. The youngest of three sons, he was born in Dunfermline Abbey to King Robert III and Annabella Drummond. His older brother David, Duke of Rothesay, died under suspicious circumstances during detention by their uncle, Robert, Duke of Albany. James' other brother, Robert, died young. Fears surrounding James's safety grew through the winter of 1405/06 and plans were made to send him to France. In February 1406, James was forced to take refuge in the castle of the Bass Rock in the Firth of Forth after his escort was attacked by supporters of Archibald, 4th Earl of Douglas. He remained at the castle until mid-March, when he boarded a vessel bound for France. On 22 March, an English vessel captured the ship and delivered the prince to Henry IV of England. The ailing Robert III died on 4 April and the 11-year-old James, now the uncrowned King of Scots, would not regain his freedom for another eighteen years.

James was educated well during his imprisonment in England, where he was often kept in the Tower of London, Windsor Castle, and other English castles. He seems to have been generally well-treated, and he developed a respect for English methods of governance. James joined Henry V of England in his military campaigns in France between 1420 and 1421. His cousin, Murdoch Stewart, Albany's son, who had been an English prisoner since 1402, was traded for Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland, in 1416. However, Albany refused to negotiate for James's release. James married Joan Beaufort, daughter of the Earl of Somerset, in February 1424. This was just before his release in April. The king's re-entry into Scottish affairs was not altogether popular, since he had fought on behalf of Henry V in France and at times against Scottish forces. Noble families now faced increased taxes to cover the ransom payments, and would also have to provide family hostages as security. James, who excelled in sports such as wrestling and tennis, literature, and music, also strongly desired to impose law and order on his subjects. Sometimes he applied such order selectively. (Full article...)

Tibbers Castle is a motte-and-bailey castle overlooking a ford across the River Nith in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. To the east is the village of Carronbridge and to the north west is a 16th-century country house, Drumlanrig Castle.

Possibly built in the 12th or 13th century, Tibbers was first documented in 1298 at which point the timber castle was replaced by a stone castle. It was the administrative centre of the barony of Tibbers until the second half of the 14th century when it shifted to nearby Morton. During the Anglo-Scottish Wars of the early 14th century the castle was captured by first the Scots under Robert the Bruce and then the English, before returning to Scottish control in 1313. (Full article...)

Robert White (1688 – 1752) was an early American physician, military officer, pioneer, and planter in the Colony of Virginia.

White was born in Scotland, the son of John White, a physician practicing in Paisley, Renfrewshire. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and later served as a surgeon with the rank of captain in the Royal Navy of the Kingdom of Great Britain. He relocated to the Thirteen Colonies between 1720 and 1730, first to Delaware, then Pennsylvania, and finally as a "pioneer settler" in present-day Frederick County, Virginia between 1732 and 1735. White was one of two physicians practicing in Frederick County, and conducted his practice from his residence near Great North Mountain. White was part of a larger wave of Scottish physicians who settled in Virginia prior to the American Revolutionary War. (Full article...)

White was born in Scotland, the son of John White, a physician practicing in Paisley, Renfrewshire. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and later served as a surgeon with the rank of captain in the Royal Navy of the Kingdom of Great Britain. He relocated to the Thirteen Colonies between 1720 and 1730, first to Delaware, then Pennsylvania, and finally as a "pioneer settler" in present-day Frederick County, Virginia between 1732 and 1735. White was one of two physicians practicing in Frederick County, and conducted his practice from his residence near Great North Mountain. White was part of a larger wave of Scottish physicians who settled in Virginia prior to the American Revolutionary War. (Full article...)

James Innes (c. 1700 – 5 September 1759) was an American military commander and political figure in the Province of North Carolina who led troops both at home and abroad in the service of the Kingdom of Great Britain. Innes was given command of a company of North Carolina's provincial soldiers during the War of Jenkins' Ear, and served as Commander-in-Chief of all colonial soldiers in the Ohio River Valley in 1754 during the French and Indian War. After resigning his commission in 1756, Innes retired to his home on the Cape Fear River. A bequest made by Innes upon his death lead to the establishment of Innes Academy in Wilmington, North Carolina. (Full article...)

Donkey Punch (also referred to as Donkey Punch: A Cal Innes book and Sucker Punch) is a crime novel by Scottish author Ray Banks. It was first published in the United Kingdom by Edinburgh-based company Birlinn Ltd in 2007, and again by the same publisher in 2008. In the United States it was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2009, titled Sucker Punch, and was reprinted in 2011.

Donkey Punch is part of a series following protagonist Cal Innes, a former convict and private investigator. Innes agrees to accompany a novice boxer from England to a fight in Los Angeles, California. While there, Innes must investigate the subsequent kidnapping of the boxer, while battling his own internal struggles and avoiding trouble with the Los Angeles Police Department. (Full article...)

Donkey Punch is part of a series following protagonist Cal Innes, a former convict and private investigator. Innes agrees to accompany a novice boxer from England to a fight in Los Angeles, California. While there, Innes must investigate the subsequent kidnapping of the boxer, while battling his own internal struggles and avoiding trouble with the Los Angeles Police Department. (Full article...)

Women in early modern Scotland, between the Renaissance of the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of industrialisation in the mid-eighteenth century, were part of a patriarchal society, though the enforcement of this social order was not absolute in all aspects. Women retained their family surnames at marriage and did not join their husband's kin groups. In higher social ranks, marriages were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations in which women as matchmakers or mothers could play a major part. Women were a major part of the workforce, with many unmarried women acting as farm servants and married women playing a part in all the major agricultural tasks, particularly during harvest. Widows could be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading, but many at the bottom of society lived a marginal existence.

Women had limited access to formal education and girls benefited less than boys from the expansion of the parish school system. Some women were taught reading, domestic tasks, but often not writing. In noble households some received a private education and some female literary figures emerged from the seventeenth century. Religion may have been particularly important as a means of expression for women and from the seventeenth century women may have had greater opportunities for religious participation in movements outside of the established kirk. Women had very little legal status at the beginning of the period, unable to act as witnesses or legally responsible for their own actions. From the mid-sixteenth century they were increasingly criminalised, with statutes allowing them to be prosecuted for infanticide and as witches. Seventy-five per cent of an estimated 6,000 individuals prosecuted for witchcraft between 1563 and 1736 were women and perhaps 1,500 were executed. As a result, some historians have seen this period as characterised by increasing concern with women and attempts to control and constrain them. (Full article...)

John George McTavish (c. 1778 – 20 July 1847, also spelled Mactavish) was a Scottish-born fur trader who played a significant role in the North West Company's activities in North America during the early 19th century. He entered the North American fur trade in 1798 with the North West Company, wherein he challenged the monopoly of the Hudson's Bay Company. Personal controversies arose from his marriages, notably abandoning his common-law wife Matooskie, an Indigenous Canadian woman, for Catherine Aitken Turner, sparking condemnation and rumours.

In the 1830s, his health declined. He died in 1847, leaving his estate to daughters from both marriages. (Full article...)

Urquhart Castle (/ˈɜːrkərt/ UR-kərt; Scottish Gaelic: Caisteal na Sròine) is a ruined castle that sits beside Loch Ness in the Highlands of Scotland. The castle is on the A82 road, 21 kilometres (13 mi) south-west of Inverness and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) east of the village of Drumnadrochit.

The present ruins date from the 13th to the 16th centuries, though built on the site of an early medieval fortification. Founded in the 13th century, Urquhart played a role in the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 14th century. It was subsequently held as a royal castle and was raided on several occasions by the MacDonald Earls of Ross. The castle was granted to the Clan Grant in 1509, though conflict with the MacDonalds continued. Despite a series of further raids the castle was strengthened, only to be largely abandoned by the middle of the 17th century. Urquhart was partially destroyed in 1692 to prevent its use by Jacobite forces, and subsequently decayed. In the 20th century, it was placed in state care as a scheduled monument and opened to the public: it is now one of the most-visited castles in Scotland and received 547,518 visitors in 2019. (Full article...)

Rusco Tower, sometimes called Rusco Castle, is a tower house near Gatehouse of Fleet in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. Built around 1500 for Mariota Carson and her husband Robert Gordon, on lands given to them by her father, it was used to incarcerate a number of the Gordons' rivals in the 16th century. After Robert Gordon died and Carson remarried, their eldest son James Gordon seized the tower and imprisoned his mother, fearing that she would make it over to her new husband, Thomas Maclellan of Bombie. Gordon went on to kill Maclellan on the High Street in Edinburgh, while a court case intended to settle the matter was ongoing.

The Gordons sold the tower in the 17th century, and it was inhabited continuously until the late 19th or early 20th century. By the middle of the 20th century the building was uninhabited and had fallen into a state of disrepair. In 1971 it was designated a Category A listed building, and was shortly afterwards purchased and renovated by Graham Carson, a Scottish businessman, who went on to live in it from 1979 until 2006. Carson attempted to discover whether his family was related to the Carsons who originally owned the estate, but was unable to document a connection. It remains in the Carson family, and is still used as a domestic dwelling. (Full article...)

Landscape painting in Scotland includes all forms of painting of landscapes in Scotland since its origins in the sixteenth century to the present day. The earliest examples of Scottish landscape painting are in the tradition of Scottish house decoration that arose in the sixteenth century. Often said to be the earliest surviving painted landscape created in Scotland is a depiction by the Flemish artist Alexander Keirincx undertaken for Charles I.

The capriccios of Italian and Dutch landscapes undertaken as house decoration by James Norie and his sons in the eighteenth century brought the influence of French artists such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. Students of the Nories included Jacob More, who produced Claudian-inspired landscapes. This period saw a shift in attitudes to the Highlands and mountain landscapes to interpreting them as aesthetically pleasing exemplars of nature. Watercolours were pioneered in Scotland by Paul Sandby and Alexander Runciman. Alexander Nasmyth has been described as "the founder of the Scottish landscape tradition", and produced both urban landscapes and rural scenes that combine Claudian principles of an ideal landscape with the reality of Scottish topography. His students included major landscape painters of the early nineteenth century such as Andrew Wilson, the watercolourist Hugh William Williams, John Thompson of Duddingston, and probably the artists that would be most directly influenced by Nasmyth, John Knox. In the Victorian era, the tradition of Highland landscape painting was continued by figures such as Horatio McCulloch, Joseph Farquharson and William McTaggart, described as the "Scottish Impressionist". The fashion for coastal painting in the later nineteenth century led to the establishment of artist colonies in places such as Pittenweem and Crail. (Full article...)

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (31 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart making him the grandson of James VII and II, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1766 as Charles III. During his lifetime, he was also known as "the Young Pretender" and "the Young Chevalier"; in popular memory, he is known as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Born in Rome to the exiled Stuart court, he spent much of his early and later life in Italy. In 1744, he travelled to France to take part in a planned invasion to restore the Stuart monarchy under his father. When the French fleet was partly wrecked by storms, Charles resolved to proceed to Scotland following discussion with leading Jacobites. This resulted in Charles landing by ship on the west coast of Scotland, leading to the Jacobite rising of 1745. The Jacobite forces under Charles initially achieved several victories in the field, including the Battle of Prestonpans in September 1745 and the Battle of Falkirk Muir in January 1746. However, by April 1746, Charles was defeated at Culloden, which effectively ended the Stuart cause. Although there were subsequent attempts such as a planned French invasion in 1759, Charles was unable to restore the Stuart monarchy. (Full article...)

Lists of featured content

| This is a list of recognized content, updated weekly by JL-Bot (talk · contribs) (typically on Saturdays). There is no need to edit the list yourself. If an article is missing from the list, make sure it is tagged (e.g. {{WikiProject Scotland}}) or categorized correctly and wait for the next update. See WP:RECOG for configuration options. |

Featured articles

- Áedán mac Gabráin

- Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652)

- Anne, Queen of Great Britain

- Anne of Denmark

- HMS Argus (I49)

- Japanese battleship Asahi

- Battle of Blenheim

- Blue men of the Minch

- William Bruce (architect)

- William Speirs Bruce

- Burke and Hare murders

- Burnt Candlemas

- Constantine II of Scotland

- Cullen House

- David I of Scotland

- Walter Donaldson (snooker player)

- Donnchadh, Earl of Carrick

- Alec Douglas-Home

- Battle of Dunbar (1650)

- Edward I of England

- Elgin Cathedral

- Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

- Fauna of Scotland

- From the Doctor to My Son Thomas

- Rachel Chiesley, Lady Grange

- Margaret Macpherson Grant

- Great North of Scotland Railway

- Bryan Gunn

- Battle of Halidon Hill

- HMS Hood

- Battle of Inverkeithing

- James II of England

- James VI and I

- Jocelin of Glasgow

- Kelpie

- John Knox

- Elizabeth Maitland, Duchess of Lauderdale

- Gregor MacGregor

- Mary, Queen of Scots

- Murray Maxwell

- William McGregor (football)

- Nebula Science Fiction

- Neilston

- Nuckelavee

- Order of the Thistle

- Pitfour estate

- HMS Ramillies (07)

- Renewable energy in Scotland

- Representative peer

- HMS Royal Oak (08)

- Scotland in the High Middle Ages

- Scotland national football team

- Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

- Shapinsay

- Isle of Skye

- Charlotte Stuart, Duchess of Albany

- HMS Vanguard (23)

- Second War of Scottish Independence

- John Wark

- Westminster Assembly

- John Michael Wright

Former featured articles

Good articles

- A82 road

- 2001 Scottish Masters

- 2002 Scottish Masters

- 2014 Scottish Labour leadership election

- 2022 Aberdeen City Council election

- 2022 Aberdeenshire Council election

- 2022 Angus Council election

- 2022 Argyll and Bute Council election

- 2022 Clackmannanshire Council election

- 2022 East Ayrshire Council election

- 2022 Glasgow City Council election

- 2022 North Ayrshire Council election

- 2022 South Ayrshire Council election

- 2022 South Lanarkshire Council election

- Aberdeen F.C.

- Aberdeen F.C.–Rangers F.C. rivalry

- Aberdour Castle

- William Adam (architect)

- Arbroath

- Architecture of Scotland

- Architecture in early modern Scotland

- Architecture in modern Scotland

- Architecture of Scotland in the Industrial Revolution

- Architecture of Scotland in the Middle Ages

- Architecture of Scotland in the Roman era

- Architecture of Scotland in the prehistoric era

- Isle of Arran

- Art in Medieval Scotland

- Art in early modern Scotland

- Art in modern Scotland

- James Balfour (died 1845)

- John Barrowman

- Battle of Barry

- Jim Baxter

- Ian Begg (architect)

- Ben Nevis

- Lewis Benson (boxer)

- Guy Berryman

- The Bhoys from Seville

- Billy Boys

- The Black Island

- HMS Bonaventure (31)

- Boobrie

- Eilley Bowers

- Bill Bowman (Scottish politician)

- British people

- Gordon Brown

- Brownie (folklore)

- Alexander Buchan (artist)

- Calendar (New Style) Act 1750

- James Campbell (British Army officer, died 1745)

- Camus Cross

- Thomas Carlyle

- Castles in Scotland

- Celtic F.C. in European football

- Celtic Park

- Erik Chisholm

- Church architecture in Scotland

- Winston Churchill

- Clan Maclachlan

- Clydesdale horse

- HMS Conqueror (1911)

- The Cookery Book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie

- Coxton Tower

- Craigiehall

- Lord Ninian Crichton-Stuart

- Cruachan Power Station

- Cullen Old Church

- 1966 European Cup Winners' Cup final

- The Daily Mash

- Dandie Dinmont Terrier

- Ruth Davidson

- Demographic history of Scotland

- Paul Dickov

- Mary Docherty

- Donkey Punch (novel)

- Doune Castle

- Dowhill Castle

- Dubh Artach

- Andrew Dudley

- Duncraig Castle

- Dunnottar Castle

- Dunrobin Castle

- Dunstaffnage Castle

- East Kirkton Quarry

- East Stirlingshire F.C.

- Easter Road

- Economy of Scotland in the Middle Ages

- Economy of Scotland in the early modern period

- Edinburgh Castle

- University of Edinburgh

- Edinburgh Zoo

- Education in Medieval Scotland

- Education in early modern Scotland

- Edzell Castle

- Eenoolooapik

- Eidyn

- Elcho Castle

- English invasion of Scotland (1400)

- Eriskay Pony

- Estate houses in Scotland

- 1884 FA Cup final

- Edward G. Faile

- Fairy Flag

- Falkirk Wheel

- Family in early modern Scotland

- James Ferguson, Lord Pitfour

- James Ferguson (Scottish politician)

- Finnieston Crane

- Flag of Scotland

- Flora of Scotland

- Sir Ewan Forbes, 11th Baronet

- Forglen House

- Forth Bridge

- Forth Valley Royal Hospital

- Dario Franchitti

- Château Gaillard

- Ryan Gauld

- Geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages

- Geography of Scotland in the early modern era

- Geology of Scotland

- Giffnock

- Gilli (Hebridean earl)

- Glass Swords

- The Glenlivet distillery

- Glenrothes

- Glorious Revolution in Scotland

- Government in early modern Scotland

- Government in medieval Scotland

- Isobel Gowdie

- Grey Gowrie

- John Gregorson Campbell

- Hampden Park

- Hibernian F.C.

- Highland cattle

- Highlands and Islands Alliance

- Lists of mountains and hills in the British Isles

- Hillforts in Scotland

- History of Scotland

- History of agriculture in Scotland

- Mary Hogarth

- Housing in Scotland

- How the Scots Invented the Modern World

- Leslie Hunter

- HMS Hurst Castle

- Ibrox Stadium

- 1902 Ibrox disaster

- Illieston House

- Inchdrewer Castle

- Inner Hebrides

- James Innes (British Army officer, died 1759)

- Charles Irving (surgeon)

- Islands of the Clyde

- Islay

- James I of Scotland

- Bert Jansch

- Jarlshof

- Jocky Wilson Cup

- Kelvin Scottish

- Battle of Kinghorn

- Kirkandrews, Dumfries and Galloway

- Kirkcaldy

- Kirkcudbright Tolbooth

- Labour Party of Scotland

- Johann Lamont

- Landscape painting in Scotland

- Billy Liddell

- Literature in early modern Scotland

- Kim Little

- Loch Arkaig treasure

- Loch Henry

- Lochleven Castle

- RAF Lossiemouth

- Murder of Alesha MacPhail

- Clan MacAulay

- Doris Mackinnon

- Sorley MacLean

- Richard Madden

- SS Manasoo

- James Clerk Maxwell

- Maybole Castle

- James McAvoy

- Stuart McCall

- Angus McDonald (Virginia militiaman)

- McEwan's

- Ewan McGregor

- John George McTavish

- Johnny McNichol

- Meantime (book)

- Mingulay

- Colin Mitchell

- Michelle Mone, Baroness Mone

- Monifieth

- William Montgomerie

- James Murray, Lord Philiphaugh

- Music in early modern Scotland

- John Mylne (died 1667)

- The National (Scotland)

- John Ogilby

- One Kiss

- Orkney

- Outer Hebrides

- Paisley witches

- Papa Stour

- Partick Thistle F.C.

- Portrait painting in Scotland

- Potion (song)

- Prehistoric art in Scotland

- Raasay

- RAF Machrihanish

- Ragnall ua Ímair

- Alex Raisbeck

- Rangers F.C. signing policy

- Renaissance in Scotland

- Richard Rennison

- Rockstar Dundee

- Romanticism in Scotland

- Andrew Ross (rugby union, born 1879)

- Royal Banner of Scotland

- Rusco Tower

- St Margaret's Church, Aberlour

- St Peter's Roman Catholic Church, Buckie

- St Rufus Church

- Scandinavian Scotland

- Schiehallion experiment

- Scotland during the Roman Empire

- Scotland in the Middle Ages

- Scotland in the early modern period

- Scotland in the late Middle Ages

- Scotland in the modern era

- Scotland national football team manager

- Scotland under the Commonwealth

- Scottish art

- 1999 Scottish Challenge Cup final

- 2002 Scottish Challenge Cup final

- 2007 Scottish Challenge Cup final

- Scottish Challenge Cup

- 1873–74 Scottish Cup

- 2012 Scottish Cup final

- 2019 Scottish Open (snooker)

- 1971 Scottish soldiers' killings

- Scottish Terrier

- Scottish art in the eighteenth century

- Scottish art in the nineteenth century

- Scottish religion in the eighteenth century

- Scottish religion in the seventeenth century

- Scottish society in the Middle Ages

- Scottish society in the early modern era

- Scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow

- Sea Mither

- Bill Shankly

- Shetland

- Shieling

- Sieges of Berwick (1355 and 1356)

- Ian Smith (rugby union, born 1903)

- Jimmy Speirs

- Staffa

- Jessie Stephen

- Alexander Stoddart

- Stoor worm

- John Struthers (anatomist)

- Charles Edward Stuart

- Sundrum Castle

- Philipp Tanzer

- Tay Whale

- D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson

- Thurso

- Tibbers Castle

- Titan Clydebank

- Torf-Einarr

- Tradeston Flour Mills explosion

- Trident (UK nuclear programme)

- USS Tucker (DD-374)

- German submarine U-27 (1936)

- Urquhart Castle

- James Walker (Australian politician)

- James Walker (Royal Navy officer)

- William Middleton Wallace

- Warfare in Medieval Scotland

- Warfare in early modern Scotland

- Water bull

- West Highland White Terrier

- Robert White (Virginia physician)

- Krysty Wilson-Cairns

- Witch trials in early modern Scotland

- Andrew Wodrow

- Women in early modern Scotland

Former good articles

- Alexander Bain (inventor)

- Billy Bremner

- William Buchanan (locomotive designer)

- Canadian Gaelic

- Andrew Carnegie

- Carnoustie

- Coatbridge

- Catherine Cranston

- Arthur Conan Doyle

- Dundee United F.C.

- Steve Evans (footballer, born 1962)

- Evanton

- Forth Road Bridge

- Glasgow

- Glasgow, Paisley, Kilmarnock and Ayr Railway

- University of Glasgow

- Frank Hadden

- Halloween

- David Hume

- Jordanhill railway station

- Deborah Kerr

- Lothian Buses

- Gillian McKeith

- Andy Murray

- Picts

- Scotland

- Scots language

- Still Game

- Alec Sutherland

- Tay Bridge

- Treasure Island

- William Morrison (chemist)

Featured lists

- List of islands of Scotland

- List of Celtic F.C. managers

- List of Scottish Football League clubs

- List of Scotland international footballers

- List of Scotland ODI cricketers

- List of Scotland national football team hat-tricks

- List of Scottish football champions

- List of Scottish football clubs in the FA Cup

- PFA Scotland Players' Player of the Year

- SFWA Footballer of the Year

- Scotland national football team results (1872–1914)

- Timeline of prehistoric Scotland

- Timeline of Scottish football

Featured pictures

-

13-06-07 RaR Biffy Clyro Simon Neil 02

-

Aerial View of Edinburgh, by Alfred Buckham, from about 1920

-

Arthur-James-Balfour-1st-Earl-of-Balfour

-

CAMPBELL, George W-Treasury (BEP engraved portrait)

-

Charles Robert Leslie - Sir Walter Scott - Ravenswood and Lucy at the Mermaiden's Well - Bride of Lammermoor

-

Common seal (Phoca vitulina) 2

-

Dalziel Brothers - Sir Walter Scott - The Talisman - Sir Kenneth before the King

-

Daniel Craig McCallum by The Brady National Photographic Art Gallery

-

David Livingstone by Thomas Annan

-

Dunrobin Castle -Sutherland -Scotland-26May2008 (2)

-

Edinburgh Castle from Grass Market

-

Eilean Donan Castle, Scotland - Jan 2011

-

Falkirk Wheel Timelapse, Scotland - Diliff

-

FalkirkWheelSide 2004 SeanMcClean

-

Gavin Hamilton - Coriolanus Act V, Scene III edit2

-

Jaguar at Edinburgh Zoo

-

Jeremiah Gurney - Photograph of Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosa

-

Loch Torridon, Scotland

-

Mount Stuart House 2018-08-25

-

N. M. Price - Sir Walter Scott - Guy Mannering - At the Kaim of Derncleugh

-

NEWScotland-2016-Aerial-Blackness Castle 01

-

Nils Olav inspects the Kings Guard of Norway after being bestowed with a knighthood at Edinburgh Zoo in Scotland

-

Paisley Abbey Interior East

-

Paisley Abbey from the south east

-

Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Alexis Simon Belle

-

Robert William Thomson - Illustrated London News March 29 1873

-

Scotland-2016-West Lothian-Hopetoun House 02

-

Sgùrr nan Gillean from Sligachan, Isle of Skye, Scotland - Diliff

-

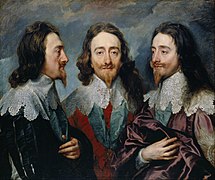

Sir Anthony Van Dyck - Charles I (1600-49) - Google Art Project

-

St Matthew's Church - Paisley - Interior - 5

-

Synthetic Production of Penicillin TR1468

-

The Air Ministry, 1939-1945. CH10270 – Edit 1

-

The Monarch of the Glen, Edwin Landseer, 1851

-

The Skating Minister

-

Thomas Keene in Macbeth 1884 Wikipedia crop

-

View of loch lomond

-

Wemyss Bay railway station concourse 2018-08-25 2

-

William John Macquorn Rankine by Thomas Annan

Get involved

For editor resources and to collaborate with other editors on improving Wikipedia's Scotland-related articles, see WikiProject Scotland.

To get involved in helping to improve Wikipedia's Scotland related content, please consider doing some of the following tasks or joining one or more of the associated Wikiprojects:

- Visit the Scottish Wikipedians' notice board and help to write new Scotland-related articles, and expand and improve existing ones.

- Visit Wikipedia:WikiProject Scotland/Assessment, and help out by assessing unrated Scottish articles.

- Add the Project Banner to Scottish articles around Wikipedia.

- Participate in WikiProject Scotland's Peer Review, including responding to PR requests and nominating Scottish articles.

- Help nominate and select new content for the Scotland portal.

Do you have a question about The Scotland Portal that you can't find the answer to?

Post a question on the Talk Page or consider asking it at the Wikipedia reference desk.

Related portals

Wikipedia in other relevant languages

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikispecies

Directory of species -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wikivoyage

Free travel guide -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus