Berkeley Pit

| Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area | |

|---|---|

| Superfund site | |

Berkeley Pit (center) and Yankee Doodle Tailings Pond (upper left) with terraced levels/access roadways. The city of Butte is at lower right. | |

| Geography | |

| City | Butte |

| County | Silver Bow |

| State | Montana |

| Coordinates | 46°01′N 112°31′W / 46.02°N 112.51°W |

Location in the United States Location in Montana | |

| Information | |

| CERCLIS ID | MTD980502777 |

| Contaminants | Arsenic, cadmium, copper, zinc, lead |

| Progress | |

| Proposed | 30 December 1982 |

| Listed | 8 September 1983 |

| List of Superfund sites | |

The Berkeley Pit is a former open pit copper mine in the western United States, located in Butte, Montana. It is one mile (1.6 km) long by one-half mile (800 m) wide, with an approximate depth of 1,780 feet (540 m). It is filled to a depth of about 900 feet (270 m) with water that is acidic (4.1 - 4.5 pH level), about the acidity of beer or tomatoes.[1] As a result, the pit is laden with heavy metals and dissolved metals that leach from the rock in a natural process known as acid rock drainage. This includes but is not limited to copper, arsenic, cadmium, zinc, and sulfuric acid.

The mine was opened in 1955 and operated by the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, and later by the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO), until its closure on April, 22 in 1982.[2] When the pit was closed, the water pumps in the nearby Kelley Mine, 3,800 ft (1,200 m) below the surface, were turned off, and groundwater began to slowly fill the Berkeley Pit, rising at about the rate of one foot (30 cm) per month. Since its closure, the water level in the pit has risen to within 150 feet (46 m) of the natural water table.[citation needed]

The Berkeley Pit is part of the largest Superfund complexes in the United States. The water, with dissolved oxygen, allows pyrite and sulfide minerals in the ore and wall rocks to decay, releasing acid. The acidic water in the pit carries a heavy load of dissolved heavy metals. A water treatment plant has been operating since October 2019.[citation needed]

The Berkeley Pit is a tourist attraction.[citation needed]

History[edit]

The underground Berkeley Mine was located on a prominent vein extending to the southeast from the main Anaconda vein system. When open pit mining operations began in July 1955, near the Berkeley Mine shaft, the older mine gave its name to the pit. The open-pit style of mining superseded underground operations because it was far more economical and much less dangerous than underground mining.

Within the first year of operation, the pit extracted 17,000 tons of ore per day at a grade of 0.75% copper. Ultimately, about 1,000,000,000 tons of material were mined from the Berkeley Pit. Copper was the principal metal produced, although other metals were also extracted, including silver and gold.[3]

Two communities and much of Butte's previously crowded east side were consumed by land purchases to expand the pit during the 1970s.[4] The Anaconda Company bought the homes, businesses and schools of the working-class communities of Meaderville, East Butte, and McQueen, east of the pit site. Many of these homes were either destroyed, buried, or moved to the southern end of Butte. Residents were compensated at market value for their acquired property.[citation needed]

Pollution, toxicity, and cleanup[edit]

The Berkeley Pit is located within the Butte Mine Flooding Operable Unit, a part of the Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site.[5] The pit itself was added to the federal Superfund site list in 1987. The Berkeley Pit is a low spot and acts like a sump for contaminated water. For this reason, it is currently an active part of the remedy for this operable unit.[6]

A waterfowl protection program began in 1996 after a flock of snow geese was discovered deceased on the pit by researchers performing water quality testing. A total of 342 carcasses were recovered.[7] ARCO, the custodian of the pit, denied that the toxic water caused the death of the geese, attributing the deaths to an acute aspergillosis infection that may have been caused by a grain fungus, as substantiated by Colorado State University necropsy findings.[7] These findings were disputed by the State of Montana on the basis of its own lab tests.[7] Necropsies showed their esophagi were lined with burns and sores from exposure to acidic metalliferous water.

On November 28, 2016, upwards of 60,000 snow geese landed in the pit during inclement weather. Once discovered, officials made efforts to haze the birds off of the pit's water and prevent more from landing in the area. An official report issued in 2017 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that the 3,000 to 4,000 snow geese that died succumbed due to gorge drinking the acidic metalliferous water.[8]

After this event, Atlantic Richfield (AR) and Montana Resources (MR) further enhanced the waterfowl protection efforts which had been in place since 1996. A new Waterfowl Protection Plan was developed and allowed for adaptive management, testing, and incorporation new tools and techniques. Deterrents such as Phoenix Wailers, a type of noise machine, and propane cannons that mimic gunshots are placed around the rim of the pit to keep birds from landing.[9][10] When waterfowl do land on the surface of the pit, personnel use firearms, hand-held lasers, and unmanned craft to haze them.[11]

A pilot project was initiated in 2019 and began treating and releasing Berkeley Pit water into Silver Bow Creek at the confluence with Blacktail Creek. This was done to protect the local groundwater from eventually becoming contaminated by rising pit water.[12] The plant cost $19 million and was designed to treat ten million gallons of water per day.[13]

Important dates[edit]

- 1994 – September, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)/DEQ issue Record of Decision (ROD) for Butte Mine Flooding Operable Unit.[14]

- 1996 – April, Montana Resources (MR) and ARCO divert Horseshoe Bend (HSB) drainage water away from Berkeley Pit to slow filling rate, per ROD. [15]

- 2000 – July, MR suspends mining operations due to high energy costs; HSB water allowed to flow back into pit, increasing pit filling rate. [15]

- 2002 – March, US EPA and Montana Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) enter into a Consent Decree with BP/ARCO and the Montana Resources Group (known as the Settling Defendants) for settlement of past and future costs for this site. [16]

- 2002 (mid/late) – US EPA and MDEQ issue order for Settling Defendants to begin design of water treatment plant for HSB water. Settling Defendants issue contract and begin construction of treatment plant. [17]

- 2003 – November, MR resumes mining operations.[15]

- 2003 – November 17, HSB water treatment plant comes on line slowing pit filling rate.[15]

Geography[edit]

The mine is at 46°00′56″N 112°30′37″W / 46.01556°N 112.51028°W, at an altitude of 4,698 feet (1432 m) above mean sea level.

Geology[edit]

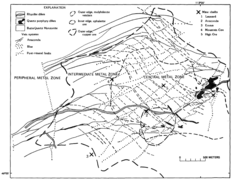

The Butte mining district is characterized by the Late Cretaceous Boulder batholith which metamorphosed surrounding rocks during the Laramide orogeny. Ore formation occurred with the intrusion of the Butte quartz monzonite pluton.[18] Mining of sulfide minerals began in the district in 1864. Placer deposits were mined out by 1867. Silver vein lodes were then the most productive until copper was discovered in 1881. Open-pit mining started in 1955. Copper has historically been the main metal produced, though lead, zinc, manganese, silver and gold have been produced at various times.[18]

-

Geologic cross section

-

Butte District geologic map

-

Mineral zones

Organisms in the water[edit]

A protozoan species, Euglena mutabilis, was found to reside in the pit by Andrea A. Stierle and Donald B. Stierle, and the protozoans have been found to have adapted to the harsh conditions of the water.[19] Intense competition for the limited resources caused these species to evolve the production of highly toxic compounds to improve survivability; natural products such as berkeleydione, berkeleytrione,[20] and berkelic acid[21] have been isolated from these organisms which show selective activity against cancer cell lines. Some of these species ingest metals and are being investigated as an alternative means of cleaning the water.

Photos[edit]

-

The Berkeley Pit mine in Butte Montana.

-

The Berkeley Pit mine in Butte Montana.

-

The Berkeley Pit mine in Butte Montana.

See also[edit]

- Auditor (dog)

- Chemocline

- Dark Money

- List of Superfund sites in Montana

- Water pollution in the United States

- Bingham Canyon Mine (in Utah)

References[edit]

- ^ Gammons & Icopini 2020 "Improvements to the Water Quality of the Berkeley Pit due to Copper Recovery and Sludge Disposal". Mine Water and the Environment, 2020.

- ^ "Anaconda to abandon Butte mine". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. April 24, 1982. p. 4A.

- ^ "Berkeley Pit History". Colorado State University, Department of Biology. Archived from the original on 2009-04-28. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- ^ Thornton, Tracy (March 13, 2016). "McQueen photographs evoke bittersweet memories". Montana Standard. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ^ "NASA - Berkeley Pit: Butte, Montana". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ "Protective Water Level". PitWatch. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c Adams, Duncan (December 11, 1995). "Did toxic stew cook the goose?". High Country News. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Dunlap, Susan (April 18, 2017). "Metals, acid in Berkeley Pit water killed geese, report confirms". Montana Standard. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Guarino, Ben (December 7, 2016). "Thousands of Montana snow geese die after landing in toxic, acidic mine pit". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Migratory birds shooed away by drone, fireworks, lasers". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. September 16, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Saks, Nora (10 April 2020). "Most Montana Superfund Work Continues Despite Stay-At-Home Directive". Montana Public Radio. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Saks, Nora (2 October 2019). "Butte Reaches Superfund Milestone, Releasing Berkeley Pit Water Into Silver Bow Creek". Montana Public Radio. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Emeigh, John (7 August 2019). "Berkeley Pit water treatment plant is almost operational". kpax.com. KPAX-TV. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency. (1994). EPA Superfund Record of Decision: Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area. Retrieved from https://semspub.epa.gov/work/08/1164465.pdf

- ^ a b c d Gammons, C.H., & Duaime, T.E. (2020). The Berkeley Pit and surrounding mine waters of Butte. Geology of Montana--Special Topics: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication, 122. Retrieved from https://mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf/geologyvolume/GammonsDuaimeMineWatersFinal.pdf

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency (2002, March 25). United States and Montana Reach Agreement with Mining Companies to Clean Up Berkeley Pit. [Press release] https://www.epa.gov/archive/epapages/newsroom_archive/newsreleases/746732fc9e0255f185256b88005adc40.html

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Montana Department of Environmental Quality. (2002). Explanation of Significant Differences: Butte Mining Flooding Operable Unit Silver Bow Creek/Butte Area NPL Site. https://semspub.epa.gov/work/08/1140014.pdf

- ^ a b Edwin W. Tooker (1990). Gold in the Butte District, Montana in USGS Bulletin 1857 Gold in Copper Porphyry Copper Systems. United States Government Printing Office. p. E17-E27.

- ^ Gugliotta, Guy (2007-08-21). "Researchers Hope Creatures From Black Lagoon Can Help Fight Cancer". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ^ Stierle, DB; Stierle, AA; Hobbs, JD; Stokken, J; Clardy, J (2004). "Berkeleydione and Berkeleytrione, New Bioactive Metabolites from an Acid Mine Organism". Organic Letters. 6 (6): 1049–1052. doi:10.1021/ol049852k. PMID 15012097.

- ^ Stierle, AA; Stierle, DB; Kelly, K (2006). "Berkelic Acid, A Novel Spiroketal with Selective Anticancer Activity from an Acid Mine Waste Fungal Extremophile". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 71 (14): 5357–5360. doi:10.1021/jo060018d. PMID 16808526.

Further reading[edit]

- Leech, Brian (2011). "Boom, Bust, and the Berkeley Pit: How Insiders and Outsiders Viewed the Mining Landscape of Butte, Montana". IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 37 (1–2): 153–170. JSTOR 23757914.

- McClave, M. A. (1973). Control and distribution of supergene enrichment in the Berkeley Pit. in Guidebook. Butte District, Montana: Butte Field Meeting of Society of Economic Geologists. pp. K–1–K–4.

- Shovers, B.; Fiege, M.; Martin, D.; Quivik, F. (1991). Butte and Anaconda revisited. Special Pub. 99. Montana: Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology.

- Weed, W. H. (1912). Geology and ore deposits of the Butte District. Professional Paper 74. Montana: U.S. Geological Survey.

External links[edit]

- Berkeley Pit Photos from the Montana Department of Environmental Quality

- PitWatch

- ISS image of Berkeley Pit (dated August 2, 2006)

- Butte, Montana toxic waste site turned tourist attraction yielding compounds that may be medically, environmentally useful

- "Casualties of Copper: The Berkeley Pit, Montana." Sometimes Interesting. 20 November 2013

- HAER No. MT-36-D, "Butte Mineyards, Berkeley Pit, Butte, Silver Bow County, MT", 3 photos, 1 color transparency, 2 photo caption pages

- 1955 establishments in Montana

- 1983 establishments in Montana

- Anaconda Copper

- Butte, Montana

- Copper mines in the United States

- Environmental disasters in the United States

- Historic American Engineering Record in Montana

- History of Montana

- Geography of Silver Bow County, Montana

- Geology of Montana

- Mines in Montana

- Open-pit mines

- Superfund sites in Montana

- Surface mines in the United States

- Tourist attractions in Butte, Montana

- 2000 disestablishments in Montana

- 2003 establishments in Montana

- Bird mortality

- Water pollution in the United States

- Former mines in the United States